Part II -DEMOCRACY VOUCHERS

To Finance Campaigns

Note: As introduced in Congress in January of 2021, the original For The People Act included a trial Voucher financing proposal to be tried in 3 states, one of them a small state. Vermont would be a perfect candidate. The legislation passed the House but was unable to pass in the Senate.

Link: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1/text

Here’s an explanation of how such vouchers could work at a local level – mostly based on Seattle.

Link: https://democracypolicy.network/agenda/open-country/open-government/democracy-vouchers

Excerpt of Policy Elements

- Establish a democracy voucher system

States can establish democracy voucher systems for state elections, such as those to elect state legislators, statewide officers (like Governor or Attorney General), and even federal offices for the state (like House and Senate seats). Below is a sketch of how a state-wide voucher system could be designed, though all variables — such as the value of each voucher, the date vouchers are sent out, and program qualification thresholds — can be changed depending on local needs.

Nine months before Election Day, every eligible resident is sent four vouchers via mail and e-mail, worth $25 each in public campaign funds. Vouchers go to any adult who can legally donate to campaigns—not solely to registered voters. Currently, all US citizens, nationals, and lawful permanent residents can donate. In Seattle, citizens and permanent residents get vouchers, as long as they are 18 by Election Day and reside in the city. In federal elections and in most states, minors can contribute to campaigns as well, so it would be reasonable for states to give vouchers to every resident 16 and older.

Residents can make use of their vouchers by:

- Assigning them to a candidate and returning them to the state through the mail (Seattle’s vouchers come with a prepaid return envelope);

- Assigning them to a candidate and submitting them to the state through an online portal; or

- Giving them to a candidate directly for that candidate to redeem. (Many candidates carry “voucher replacement forms” when canvassing, in case someone wants to contribute but doesn’t know where their physical vouchers are. The city crosschecks to make sure that no one uses more than four vouchers.)

To begin soliciting, receiving, and redeeming vouchers, candidates need to qualify for and register with the voucher program. First, candidates must demonstrate viability by receiving a certain number of donations of a certain size from a certain number of people (e.g. “at least $5 from at least 0.1% of registered voters in the area they are running to represent”). Next, candidates must formally opt-in to the program, by signing a contract with the relevant governmental body (e.g. the Seattle Ethics and Elections Commission), binding them to program rules.

After qualifying, candidates can begin redeeming vouchers they collect for public money. To reduce administrative costs, money should be given to candidates every two weeks, though the process could be quickened with a more robust digital transfers system (such as a public payments platform). Some reformers have suggested giving candidates a small grant upon qualification to help cover short-term costs before they’ve had time to raise money through vouchers (though Seattle’s program does not include this).

One concern among those newly introduced to vouchers is fraud. In reality, however, voucher fraud is no more likely than voter fraud, posing a negligible risk for future cities and states implementing vouchers. In Seattle, it is a gross misdemeanor to “buy, sell, trade, forge, steal, or otherwise misuse vouchers.” Campaigns found to have benefited from voucher fraud must return public money and may no longer be eligible for the program. Additionally, voucher assignments are transparent: Seattle provides an online portal where anyone can check who has assigned their vouchers, to which candidates, and when. These steps have made voucher fraud essentially unheard of in Seattle.

Another concern is cost. Fortunately, there are three built-in limitations on the costs of voucher systems. First, not every eligible resident will use their vouchers. In 2017 and 2019, participation rates in Seattle were 3.8% and 8.5% respectively, an increase in donor participation from before vouchers, but not a significant burden on the city’s ability to pay. Conservatively assuming 20% participation and an additional 25% overhead, our estimates suggest program costs would be less than a quarter of a percent of total state operating funds in all 50 states. Second, candidates face a cap on their total spending (as explained below), meaning there is a limit to how many vouchers any one candidate can redeem. Third, as a final stop-gap, democracy voucher programs can impose reasonable limits on total public spending. For example, before each election cycle, the Seattle Ethics & Elections Commission announces the maximum they will spend on redeemed vouchers and alerts candidates and the public if that limit is reached. The limit was not reached in 2017 or 2019.

Possible funding sources for a democracy voucher program include an allocation from the state general fund or a new levy directed specifically to the program. Seattle voters, for example, passed a 10-year property tax levy of $3 million per year to fund the program. A 2016 statewide Washington ballot initiative which would have implemented vouchers involved funding the program by repealing the non-resident sales tax exemption, which would have raised $173.2 million over 6 years.

Note: For the following parts, click on this link: https://democracypolicy.network/agenda/open-country/open-government/democracy-vouchers

- Require candidates to opt-in to additional rules before receiving public money

- Increase public awareness of the program to ensure adequate participation

- Empower local governments to implement their own democracy voucher systems

- Mitigate the impact of political action committees

APPENDIX E

VERMONT LEGISLATORS’ OATH and RELEVANT PARTS OF CONSTITUTION

The Oath of Allegiance; Oath of Office section of the Vermont Constitution.

Text of Section 56:

Oaths of Allegiance and Office

Every officer, whether judicial, executive, or military, in authority under this State, before entering upon the execution of office, shall take and subscribe the following oath or affirmation of allegiance to this State, (unless the officer shall produce evidence that the officer has before taken the same) and also the following oath or affirmation of office, except military officers, and such as shall be exempted by the Legislature.

The Oath or Affirmation of Allegiance

You do solemnly swear (or affirm) that you will be true and faithful to the State of Vermont and that you will not, directly or indirectly, do any act or thing injurious to the Constitution or Government thereof. (If an affirmation) Under the pains and penalties of perjury.

The Oath or Affirmation of Office

You do solemnly swear (or affirm) that you will faithfully execute the office of ____ for the ____ of ____ and will therein do equal right and justice to all persons, to the best of your judgment and ability, according to law.

Pertinent parts of Vermont’s Constitution

Article 6. [Officers servants of the people]

That all power being originally inherent in and co[n]sequently derived from the people, therefore, all officers of government, whether legislative or executive, are their trustees and servants; and at all times, in a legal way, accountable to them.

Article 7. [Government for the people; they may change it]

That government is, or ought to be, instituted for the common benefit, protection, and security of the people, nation, or community, and not for the particular emolument or advantage of any single person, family, or set of persons, who are a part only of that community; and that the community hath an indubitable, unalienable, and indefeasible right, to reform or alter government, in such manner as shall be, by that community, judged most conducive to the public weal.

Article 8. [Elections to be free and pure; rights of voters therein]

That all elections ought to be free and without corruption, and that all voters, having a sufficient, evident, common interest with, and attachment to the community, have a right to elect officers, and be elected into office, agreeably to the regulations made in this Constitution.

I’ll be arriving in Santa Fe,

I’ll be arriving in Santa Fe, Just before I left Vermont, I finished #4 in my Reasons to Fix Democracy podcast series. This time something near and dear to my heart having just gone through it with Sally: To fix our democracy to ensure that those who represent us establish and support a health care system that provides high quality healthcare to all 330+ million of us at the lowest, system-wide total cost, and is financially and socially sustainable into the future. I’ve got links to some great resources on this topic, and I hope you’ll take a few minutes to listen.

Just before I left Vermont, I finished #4 in my Reasons to Fix Democracy podcast series. This time something near and dear to my heart having just gone through it with Sally: To fix our democracy to ensure that those who represent us establish and support a health care system that provides high quality healthcare to all 330+ million of us at the lowest, system-wide total cost, and is financially and socially sustainable into the future. I’ve got links to some great resources on this topic, and I hope you’ll take a few minutes to listen.

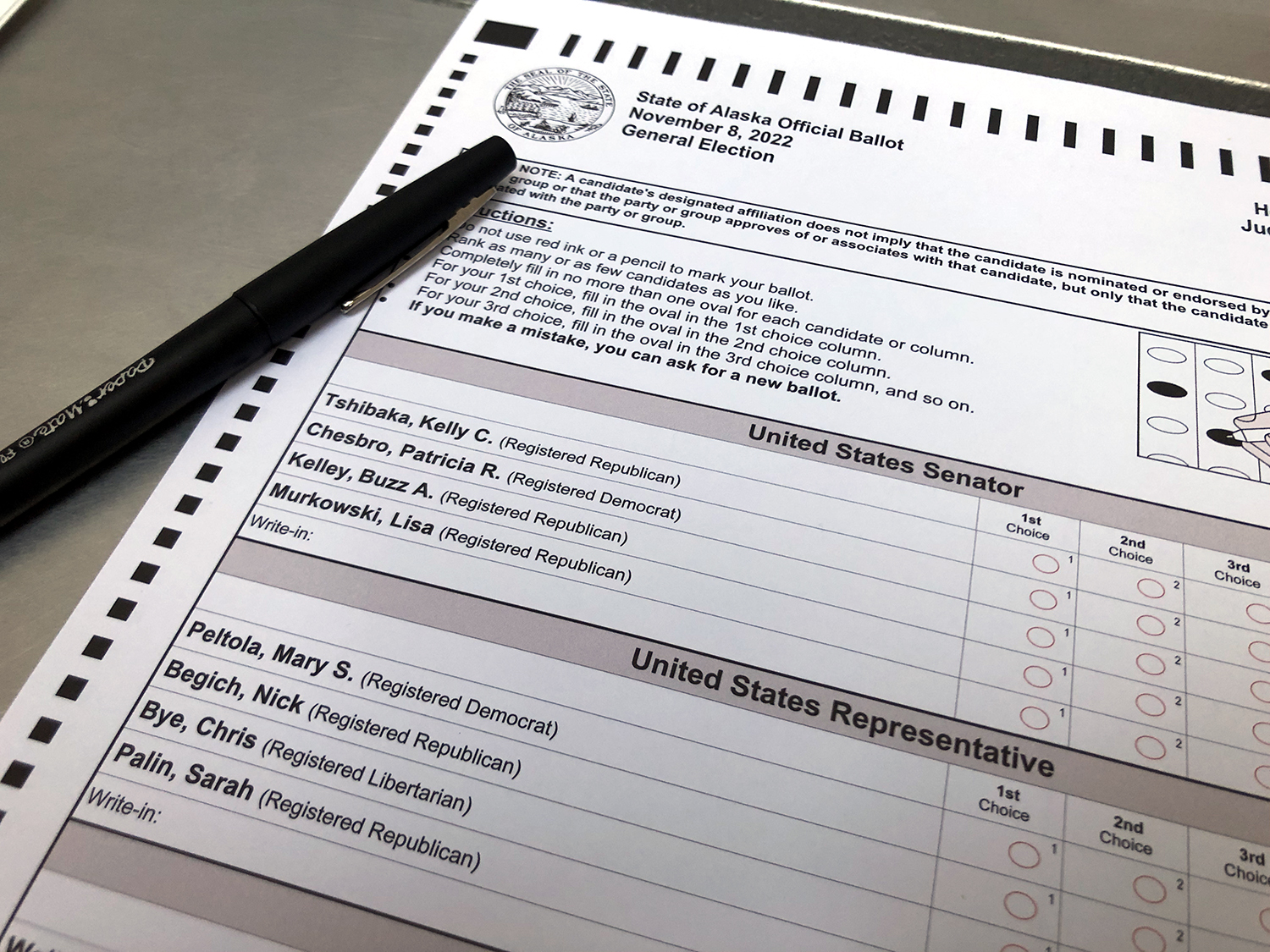

and ranked choice voting after a 2020 referendum. Like many states,

and ranked choice voting after a 2020 referendum. Like many states,